by Timo Luege, TC103: Technology for Disaster Response facilitator

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all public social media messages in a disaster would come with a flag that identifies them as relevant? The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is trying to pave the way for that with the brand new Hashtags Standards for Emergencies.

The document builds on experiences gained in the Philippines where a set of standard hashtags such as #RescuePH or #ReliefPH have become so commonly used, that the government recently endorsed these as “official” disaster response classifiers to help identify needs. OCHA is now trying to elevate this system to the global level in the hope that we will start to see more consistency across countries and disasters. If successful, this hashtag standards could help disaster responders and their supporting software systems identify needs more quickly and reduce the amount of time needed to find relevant messages in flood of updates.

OCHA proposes three different types of social media hashtags:

- Disaster title hashtags. This type of hashtag (e.g. #Sandy) would be used by anyone to generally comment on an emergency (e.g. Hurricane Sandy) and would not be actively monitored by response agencies.

- Public reporting hashtags. By suggesting a specific hashtag that citizens can report non-life-threatening emergency items they see (e.g. #311US for broken power lines or a damaged bridge in the USA), we would be making sensors of the entire population. The resulting data could be scanned, mined and filtered to the relevant responding agencies.

- Emergency response hashtags. By providing a standard hashtag to trigger emergency response, based on local standards (e.g. #911US for the USA), we would enable citizens to tag content that is absolutely critical. It would also enable responders to set up dedicated social media monitoring tools and channel the resulting information into their already existing mechanism(s). Social media would become an official information source.

(source: verity think)

I think this is great initiative and governments should pick up the ball and use this document as guidance for their own national strategies. That national authorities make this their own is essential because it can only work if the affected population knows about these hashtags in advance of the disaster and if the hashtags have been localized.

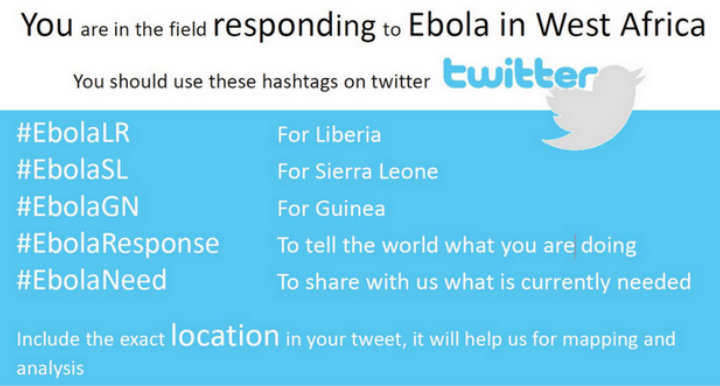

The graphic the report uses to illustrate the idea for the Ebola response is a good case in point:

The suggested hashtags seem pretty straightforward until you take into consideration that Guinea is French speaking, meaning that people there probably will use something like #EbolaBesoin instead of the English #EbolaNeed.

Of course that would still be a huge step forward, since it would increase consistency even in cases where an emergency spans multiple countries and languages. After all, a limited number of hashtags that are used in multiple languages is still much better than no system. But it also shows that this document is not so much a blueprint as a concept study. It is now up to governments and other national disaster response organizations to make it work.

Interested in learning how social media and other technologies can help with disaster response? Enroll now to lock in your early bird rate for our Technology for Disaster Response online course that begins June 22.

This post originally appeared in Social Media for Good

About the TC 103 facilitator: Timo Luege

After nearly ten years of working as a journalist (online, print and radio), Timo worked four years as a Senior Communications Officer for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in Geneva and Haiti. During this time he also launched the IFRC’s social media activities and wrote the IFRC social media staff guidelines. He then worked as Protection Delegate for International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Liberia before starting to work as a consultant. His clients include UN agencies and NGOs. Among other things, he wrote the UNICEF “Social Media in Emergency Guidelines” and contributed to UNOCHA’s “Humanitarianism in the Network Age”. Over the last year, Timo advised UNHCR- and IFRC-led Shelter Clusters in Myanmar, Mali and most recently the Philippines on Communication and Advocacy. He blogs at Social Media for Good and is the facilitator for the TechChange online course, “Technology for Disaster Response.