When is it ethical to either restrict or share information during violent conflict? Two tweets summarized the information challenges of the South Sudan Watch crisis map will face in the coming days.

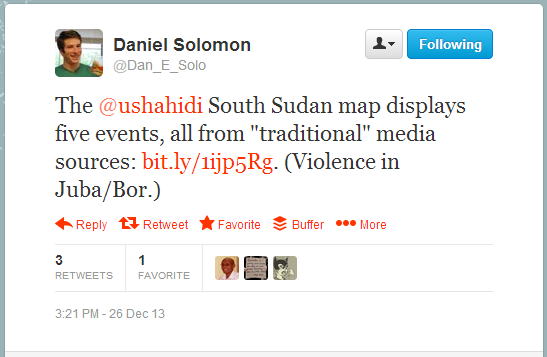

Tweet #1: Is it ethical to restrict information to the public?

As of the time of this writing, the public-facing crisis map for South Sudan Watch is still disappointingly sparse. Daniel Solomon, an expert on genocide and involved in anti-genocide networks (also author of the Securing Rights blog), observed that the crowdmap was simply capturing a handful of “traditional” media reports instead of plotting real-time incidents for the public to see.

It’s possible that the public map doesn’t yet display all the information available because it’s unclear if doing so would cause more harm than good – and that’s not an easy call to make. But is it ethical to restrict information if it could better inform humanitarian intervention or even save lives by providing information directly to those on the ground? Nathaniel Raymond would refer to as the “Right to Information in Disaster,” with information being as valuable as food, water, shelter, and medicine.

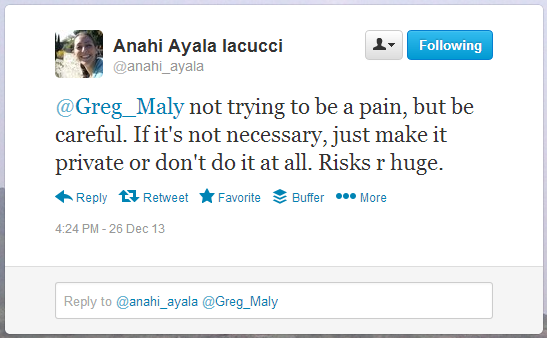

Tweet #2: Is it ethical to reveal information about the vulnerable?

But experienced crisis mappers have already begun to weigh in on how dangerous sharing this information can be — especially without sufficient context. in a post on “The Conundrum of Digital Humanitarianism: When the Crowd Does Harm” Anahi (a co-founder of the Standby Task Force) cautions:

“But the truth is that the beauty of the internet, in humanitarian crisis, is also its curse: everyone can do everything and does not need to be “trained” or to be a “professional”, or to be part of a formal organization.”

Fortunately, there are opportunities for a middle ground. Organizations such as UN-OCHA can become what Patrick Meier terms an “Information DJ,” combining external information with input from local tech-savvy communities. However, Meier too warns that “enthusiasm for new technology doesn’t overtake ethical and humanitarian accountability principles around informed consent, data privacy, and do no harm.”

Conclusion:

It’s unclear at this point which information will be shared or even if the map will stay available to the public (or if a bounded and bifurcated public/private method is better suited to the challenge). But what is clear is that the coming challenges to crowdsourcing information for the conflict in South Sudan are not technical, but organizational and ethical.

—

Interested in learning more on this topic from conflict management experts around the world? Join our online course on the role of technology in addressing conflicts in South Sudan and other parts of the world including Kenya, Syria, Uganda and Myanmar. Apply now to join this January 13 – February 7 course.