By Michael Baldassaro, Innovation Director at Democracy International

On Sunday October 26, 2014, more than three million Tunisian voters cast ballots in parliamentary elections, marking an historic milestone in the country’s remarkable transition from authoritarian rule to democracy. To support the election process, international and Tunisian civil society organizations deployed thousands of observers on Election Day.

One of the Tunisian observation groups, I Watch, recruited, trained, and deployed hundreds of observers nationwide on Election Day. While recruiting, training and deploying observers is a necessary – and human and financial resource intensive – practice in an election observation exercise, I Watch decided to take a bit of a different approach. In their own words:

“Election observation has become a costly, top-down and exclusive exercise that largely ignores citizen input and participation for legitimising the process. I Watch aims to counter this through an inclusive and technologically innovative approach which could revolutionise election observation worldwide.”

I Watch promotion for e-observation

With support from Democracy International and Ona, I Watch conducted a “hybrid pilot [that] combines domestic observation with crowdsourcing tools to provide a new way of engaging citizens in the electoral process.” As a youth-led organization with a mission to increase citizen participation in public life, I Watch set out to provide all Tunisian citizens interested in safeguarding their own elections with the opportunity and the skills to do so.

Six weeks prior to Election Day, I Watch held a press conference to launch its e-observation platform where citizens could create profiles and register to be observers. Within a week of the launch, more than 600 citizens signed up to be eligible as I Watch observers. By Election Day, 1,318 citizens from all 24 Tunisian governorates registered through the E-Observation platform, of which 1,215 were ultimately accredited as I Watch observers.

Unlike a typical election observation project, in which observers are trained face-to-face through a national day of training or series of training workshops throughout the country, I Watch produced a series of videos to educate citizen observers on the goals of election observation, the roles and responsibilities of an election observer, the opening, voting, closing and counting processes on Election Day, and instructions for transmitting observer findings.

E-Observation Training Video: What is Election Observation?

Applying an e-learning model greatly reduced the amount of human and financial resources typically associated with training observers: depending upon the size of an election observation mission, or the size of the country in which it takes place, costs for training observers can be prohibitively expensive – sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars. It also enabled observers to learn at their convenience while preserving a measure of quality control that can be lost when a training-of-trainers or step-down training approach is used.

After observers watched all the videos, they were required to take a quiz to test their

aptitude and ensure that they had understood all the necessary steps to be effective observers. If an observer passed the quiz, s/he was then accredited as an I Watch observer. If an observer didn’t failed the quiz, s/he could re-watch the videos and take

the quiz again.

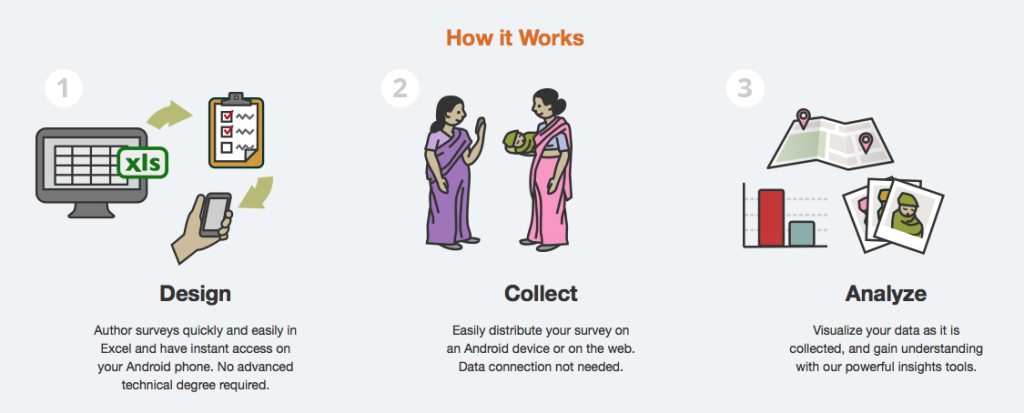

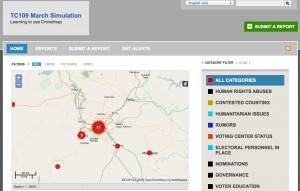

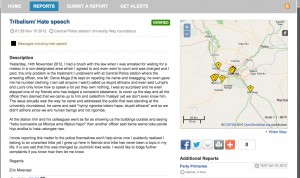

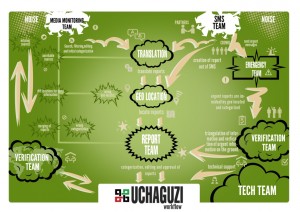

To collect and analyze observer findings, I Watch used two completely free and open-source information and communications technology (ICT) applications: Ona and SMSsync. Observers submitted their findings directly from polling stations via SMS to a customized I Watch Ona platform. I Watch established a “central data center” to analyze findings collected in real-time and proactively contact observers to collect additional information

as necessary.

Democracy International used a similar data collection toolkit called Formhub to collect and analyze data during its January 2014 election observation mission in Egypt. Through the application of key elements of election observation methodology, crowdsourcing techniques, and the use of free and open source ICTs, I Watch was able to increase citizen participation, reduce costs, and make a positive contribution to the electoral process. Given its success during the parliamentary elections, I Watch is planning to move forward with an even better exercise for the presidential elections due to take place in November 2014.

About Michael Baldassaro

Michael Baldassaro is the Innovation Director at Democracy International. Mr. Baldassaro has a decade of experience designing, managing, and implementing democracy and governance projects in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. He previously served as DI’s Tunis-based Project Director for the Middle East and North Africa, where he designed projects that use open data, new media, smartphone applications, and crowdsourcing techniques to improve the quality of elections. Before joining DI in 2012, Mr. Baldassaro worked with the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the Carter Center (TCC) to assist civil society groups in applying statistical principles to election observation using state-of-the-art information and communications technologies, such as mobile data collection technologies, data visualization tools, and social media platforms. Mr. Baldassaro holds an M.A. in International Conflict Analysis from the University of Kent at Canterbury and the Brussels School of International Studies. He is proficient in conversational French.