Makerere University is one of the oldest and most well reputed universities in East Africa. As a leading institution in the field, Makerere, or Mak (pronounced Muuk) as it’s affectionately called, has had a prolific distance learning program since the early 1990s. Much of this program followed the historical route of paper based correspondence learning until the early 2000’s.

Category: Blog

Tomorrow I’ll be giving a talk at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution on how emerging technology and crowdsourcing can enhance academic research in conflict-affected settings. The TechChange team will be there for the talk, and I’ll be live tweeting the event all day (#confresearch).

Along with my talk, we’ll also be hearing from my George Mason colleagues as they discuss the challenges of protecting their informants in high risk environments, the legal issues of doing field research on terrorist groups, and the logistics of doing research in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

For those who are in the educational and research field, my talk will also be a good opportunity to learn a little more about what TechChange will be covering in their upcoming courses New Technologies for Educational Practice and our soon-to-be-posted Social Media and Technology Tools for Research (July 23 – August 10).

This post was contributed by Ferya, a participant in the TechChange course: “Global Innovations for Global Collaboration” developed for IREX for alumni of the Global Undergraduate Exchange Program in Pakistan, a program of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, US Department of State administered by IREX. Learn more about our online course: New Technologies for Educational Practice

After going through our first class’ assigned reading “How mGive used texting to raise $40 million for Haiti“, I realised how technology can help us do wonders. I myself have experienced a similar thing in the year 2005. Though it was not exactly the same but the main idea was closely similar.

On October 5 – 2005, Pakistan’s northern areas were hit by an earthquake of 7.6 magnitude, which left around 80,000 people dead and 100,000 injured. The earthquake is said to be the 17th deadliest earthquake the Earth has ever seen.

I was a high school student then and was very disturbed by the occurrence. It was something I had never seen in my life before and was very shaken. I wanted to do something to help my fellow citizens but really did not know what?

In Karachi, by evening everyone was texting each other to pray for the victims. But as time passed, people started exchanging ideas via messages of what can one do to help. People shared messages of possible food items, clothing stuff and medicines that can be donated. Addresses of various donation camps were exchanged throughout. A number of telethons were broadcast with celebrities asking people within the country and abroad, to help the people of the affected areas. Many mobile network companies also provided their services for donations via mobile phones.

The most famous and well organised camp of the city, which was set up by a known TV celebrity, was introduced to the people of the city via messages, that were circulated religiously.

The word spread and soon the camp was flooded with volunteers as young as kindergarten students and as old as those KG students’ grandparents. People of all age groups, from different social strata and from different professions brought whatever they could get for the victims. The camp stayed open 24/7 for months.

The rehabilitation work was months long and was very organised and well executed. But it would not have been a huge success without the help of the young volunteers who not only contributed in material sense but were physically available all the time for any kind of assistance. And this mobilisation became possible only because everyone was connected via mobile phones.

Apart from messages with lists of needed items, messages with motivational poetry and quotes were also exchanged which helped everyone focus on their only goal – to help, no matter how.

This article is re-posted from TechChange team member Charles Martin-Shields’s website “Espresso Politics”. We thank him for being awesome and sharing his stories from paradise with us. You can follow him at @cmartinshields.

TechChange has a course coming up that breaks a little bit from the standard “ICT4D” content. It’s titled “New Technologies for Educational Practice” and I was trying to think of how someone would put this knowledge to use. It all seemed abstract, so wracked my brain for cases when I used technology in my own educational work, which included two years in Apia, Samoa as a Peace Corps volunteer doing English curriculum development.

While there is content related to video games, web technology and social media, in the TechChange course, I wanted to try to think of a practical example of using technology to enhance learning.

As I thought back to those wistful days in Polynesian tropical paradise, I remembered that a few teachers and I came up with a fun, elegant (IMHO), solution to the problem of Samoan secondary students texting in class.

As I thought back to those wistful days in Polynesian tropical paradise, I remembered that a few teachers and I came up with a fun, elegant (IMHO), solution to the problem of Samoan secondary students texting in class.

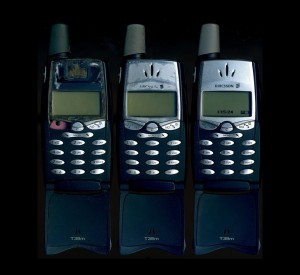

To put it in context, this was January 2007, and Samoa had just taken their digital mobile phone system online. Suddenly everyone had a GSM mobile phone and everyone was texting. Mobile telephony went from 0 – 60 in Samoa almost instantaneously. Naturally every student in grades 9-12 was texting during class, as rebellious youths are known to do.

The teachers tried the usual methods of corporal punishment, phone confiscation, and detention, but none of this seemed to deter the students from texting. So I sat down with a few of the teachers over beers and we decided, if you can’t beat them, join them.

Our solution was to make text messaging part of the English learning process. Students had the opportunity to text each other in class, read the texts (which were teacher approved), and were graded on the accuracy of their spelling and syntax. The practice sentences of 140 characters or less were easier to handle for speakers of English as a second language, compared with the higher density books, and students could practice from home.

This exercise wasn’t a replacement for the more formal learning that took place in the form of longer texts and written exams, but it provided a space for students to practice using English that was accessible and fun. While it might not have been a grand strategic shift in pedagogy, mobile technology provided a free tool to enhance the learning experience in a sustainable, enjoyable way. Of course, I’d love to see comments about all of your experiences with technology, learning and development, since we’re always learning from each other in this space!

If you’re interested in learning more about education and technology, have a look at “The New Technologies for Educational Practice” as well as our other training programs on the TechChange site.

This past Fall, I was fortunate enough to participate in an online course offered by TechChange; Mobiles for International Development – TC105. If you’re unfamiliar with TechChange, their mission is as follows: “TechChange trains leaders to leverage relevant technologies for social change.” There are several resources I look to through my contacts, social media, and research in the field of Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICT4D), and TechChange is one on which I strongly rely.

How important is formal education in this rapidly changing and growing field of tech for social change? Due to the fluid nature of technology and the necessity to apply sustainable tech solutions, where they also make sense. It’s important to have educational “institutions” where academics, but more importantly practitioners, can learn, interact and communicate on relevant topics. This serves not just as an educational forum, but a way of sharing best practices, use cases, project successes and failures. We as human beings, learn from these multifaceted approaches, both academic and experiential. Traditional education institutions have been rather slow to integrate the ICT4D discipline into formal graduate level degree programs, with a couple of exceptions at the University of Manchester and the University of Colorado – Boulder. So TechChange and their curriculum is serving to bridge the gap in education with their certificate courses. Other offerings in the TechChange catalog are listed here.

So this brings me to the title of this post, Planting Seeds. Through the TechChange blended learning environment, Twitter chats, Skype calls, etc…I was able to meet “like minded souls” already working in the social change space in Haiti. Once I found I’d be traveling to Haiti to conduct some work and assessments for our Notre Dame Haiti Program and two additional TechChange TC105 students were already working in the country, we discussed getting together for an informal lunch meeting to discuss mobile tech and more specifically, the application of FrontlineSMS in our respective programs. The seeds were planted!

Our TC105 moderator for Team Deserts, Flo Scialom (Community Manager extraordinaire of FrontlineSMS in the UK), offered her expertise in community building to help pull us, and others together. Each day, as we criss-crossed Port-au-Prince and Leogane with meetings at various ISP’s and Mobile Network Operators, I’d get an email from Flo, “Tom, do you have room for one more?”, “Do you have space for another?”…etc…The seeds were watered and nurtured!

Our TC105 moderator for Team Deserts, Flo Scialom (Community Manager extraordinaire of FrontlineSMS in the UK), offered her expertise in community building to help pull us, and others together. Each day, as we criss-crossed Port-au-Prince and Leogane with meetings at various ISP’s and Mobile Network Operators, I’d get an email from Flo, “Tom, do you have room for one more?”, “Do you have space for another?”…etc…The seeds were watered and nurtured!

So what started with three or four for an informal lunch, turned into 17 individuals, representing five continents and eight countries – and a full blown FrontlineSMS meet-up luncheon at the Babako Restaurant in Port-au-Prince. The organizations at the table represented many sectors in the aid and development community: microfinance, sexual violence, IDP camp resettlements, human rights abuses, education, and public health. It really was inspiring to look around that table and realize how many Haitians were benefiting from the dedication of these individuals and their organizations. A true force multiplier! The seeds sprout!

The talk revolved around FrontlineSMS setup, configuration and use cases, as well as other mobile and open-source tools in the social change arena, such as RapidSMS, Ushahidi, OpenMRS, openrosa, and more. So this group was not so much about a single software application, but more about affecting change with any technology – fostering a community of practice around ICT4D/M4D, and educating ourselves about opportunities for change using technology. The flower blooms!

The big win was looking around the table, as diverse as our needs and applications are; we all shared a common purpose, enthusiasm and a collective knowledge, to affect positive change with technology. It’s my hope this group will continue to grow – to blossom to include others and be self sustaining, which will amplify the positive impact for our Notre Dame Haiti Program, the other organizations at the meet-up and ultimately the Haitian people.

We’ve posted the video slideshow of our year in review, but we need your help to pick the accompanying music!

Tweet your suggestions @TechChange using #TCParty or just use the comments section below.

Suggestions from our staff:

- Bob Dylan: The Times They Are A-Changing

- Theme: 2001 A Space Odyssey

- Blind Melon: Change

- Daft Punk: Around The World

See why we need the help?

Suggestions from Twitter:

- What abt RCHP "Can't stop" ? that seems apt. @TechChange @amaniinst @neuguy #TCparty@vargheseanandAnand Varghese

- @techchange What about something by Thievery Corporation? #TCParty@cmartinshieldsCharlesMartinShields

- #tcparty 'maps' by yeah yeah yeahs, 'technologic' by daft punk, 'computer love' or 'pocket calcularor' by kraftwerk@thomandiniTaylor Thomander

- @TechChange #TCParty music suggestion: The Romantics: What I Like About You http://t.co/JFJXdJWM@neuguyChristopher Neu

On November 9, TechChange President Nick Martin and the TechChange team were invited to participate in a roundtable discussion co-hosted by the International Peace Institute and the UNDP’s Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery on crowdsourcing for conflict prevention.

The discussion covered the policy challenges associated with crowdsourcing at a national level, as well as discussions about tools and human factors. The UNDP’s Ozonnia Ojielo expertly explained the Amani 108 process in Kenya, Nick Martin and Google’s Beth Liebert spoke about communication and mapping tools involved in the process of crowdsourcing, and William Tsuma of the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict talked about the human side of crowdsourcing, including the risks people face when participating.

Ozonnia Ojielo gave the audience an in-depth analysis of why the Amani 108 program, co-managed by the UNDP and Kenyan Government, was so effective for preventing significant outbreaks of violence during the referendum vote in 2010. He explained the level of buy-in across all levels of society, and that there was both information gathering capacity and the ability to respond when needed.

Moving off this case study, Nick Martin, with the help of Jordan Hosmer-Henner, talked about the social tools for crowdsourcing, including FrontlineSMS, Twitter, and Freedom Fone. Since these systems can provide a data analyst with geographic information, the TechChange team had put together a crowdmap and provided the audience with information to text into a FrontlineSMS platform. Jordan then demonstrated how the texts are received in the crowdmap, and how to map them. This was a nice interactive touch, and allowed participants who may not have seen mapping platforms to interact briefly with the software from their seats.

Beth Liebert expanded on Nick and Jordan’s presentation, giving a detailed explanation of Google’s mapping products. She demonstrated how the maps incorporated layering technology that could be easily used by non-technical practitioners, demonstrating the platform with a map that was designed during the London riots to provide information on police activity, safe spaces and different types of events. This information is all crowdsourced using the tools that Nick and Jordan discussed, and Beth provided a superb explanation of the depth and capacity Google mapping products have for bringing data to life.

William Tsuma brought the conversation back to the operational side, speaking about the challenges of organizing crowdsourcing operations in environments where security was a problem and the issues surrounding data sharing with governments and security agencies. His suggestions demonstrated practical examples of how to work around these challenges, as well as methods that professionals could employ while working on crowdsourcing at the community level.

The discussion covered the range of issues at the policy level, covered tools and technical needs for crowdsourcing, and brought the conversation back to the core issue, that we are trying to improve the lives of people affected by conflict and instability. Roundtables like these, hosted by organizations doing good work in the field and supporting critical research on conflict prevention, provide a space to discuss the intersection of tools, policy and human challenges of crowdsourcing while giving a variety of experts the opportunity to ask questions and share their insights.

In the fall of 2011, TechChange facilitated its first series of online courses. The courses were each three weeks long and covered the following topics (we will also be running these courses again in the Spring):

- Technology Tools and Skills for Emergency Management

- Global Innovations for Digital Organizing: New Tactics for Democratic Change

- Mobile Phones for International Development: New Platforms for Public Health, Education, and Finance

Participant Demographics

In total, we had 170 participants from 43 countries and the response has been remarkably positive. Participants came from a range of organizations, including:

| Voice of America | World Bank | IREX |

| USAID | World Pulse Media | Mercy Corps |

| Plan International | Freedom House | UNDP |

| World Vision | Concern | Notre Dame |

| International Rescue Committee | International Youth Foundation | Teachers Without Borders |

| International Red Cross | Office of the First Lady of the Dominican Republic | Radio Station in Haiti (Minustah FM) |

Cross-posted from The Amani Institute Blog

The first thing Anya Kamenetz said when she took the stage at a talk at the Center for American Progress to promote her new book was: “The book is up online so feel free to surf to it on your phones and check it out”.

When was the last time you had a professor or other speaker actually encourage you to browse on the internet, on your cellphone, while he/she was talking?

This post is contributed by a guest author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of TechChange or the TechChange staff

The development of a robust state is almost always tied to education. The mode of education that has been in fashion since colonialism favors the privileged teacher entering an underprivileged area and bestowing light upon the children, or adults as it may be. There are a few problems with this, not least the fact that really good teachers don’t often go to the places they are needed most.

Two interesting experiments suggest that those teachers aren’t needed; if the tools are given to children in developing areas, they will naturally teach themselves.

Suguta Mitra has recently developed what he calls Self Organized Learning Environments (or, SOLEs), which are designed for children in groups to utilize technology (e.g. high speed Internet, video calling, etc.) for self-teaching. The SOLEs stem from smaller experiments he conducted throughout the world with children being given nothing but the tool – no instruction on how to use it, no goal – to see just how much they could learn.

The first experiment sees a computer with a broadband connection placed into a slum of India. Within weeks, the children of the town are using the computer to teach themselves…well, anything. Some use it to record music and play it back. Others download games and teach friends how to play them. In one eye-opening example, Mitra places computers in a classroom, tells Tamil-speaking 12-year old children in a South Indian village to learn biotechnology in English, on their own. He explains:

“I called in 26 children… I told them that ‘there’s some really difficult stuff on this computer, I wouldn’t be surprised if you didn’t understand anything. It’s all in English and uh, I’m going.”

He returned two months later to see just what the children had learned and one girl responds, “Apart from the fact that improper replication of the DNA molecule causes genetic disease, we’ve understood nothing else.”

The idea that such a small catalyst — the introduction of a computer to a group with no prior experience/instruction — could blossom into the development of intellectual societies driven by a preternatural instinct to learn is reminiscent of emergence theory, which maintains that simple actions lead to complex systems.

Another such example of emergence theory in education comes in Neil Gershenfeld’s Fab Labs. His project deals in relatively low-cost labs – about $20,000 each – that allow people to build the things they need using digital and analog tools. The idea is that rather than using technology as a top down equalizer, giving people the technology will allow them to create solutions for themselves.

This is beginning to rattle the foundations of emerging economies who often depend on the aid – financial or otherwise – given by established countries. Now, rather than wait for someone to offer help, they can literally create their own. It’s particularly important in places where outsiders fail to understand the cultural dynamics of an area. Mitra’s SOLEs and Gershenfeld’s Fab Labs allow local economies to create local solutions, thereby empowering themselves.

Global technology is advancing swiftly. Software and information are becoming cheaper through cloud computing, which pushes the costs down further and simultaneously creates a wireless resource that people can tap into. As the cloud broadens and the technology revolution continues, so too will the revolution in education and the way we think about developing nations.

Thomas Stone is a freelance writer and frequent contributing author at gospel(s).