The gatekeepers of gaming are suddenly in the middle of Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In the past few days, Google Play has removed several games relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, claiming that they violate Developer Program Policies. In one example, the “Bomb Gaza” game [Pictured] was removed following a social media backlash against a game that appeared to reward dropping bombs on Gaza from an Israeli jet. While the app comments for Google Play ranged in perspective from criticism to support, media reports described the game as seemingly intending to offend, including matching a rating appropriate for children with a mandate for killing civilians as well as insurgents.

There’s no guarantee that the game won’t reappear. Even after similar outrage shut down an “Angry Trayvon” game about the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, you can still find games like Angry Trayvon: Revenge available for download on Google Play. And even if gatekeepers such as Apple and Google refuse to grant access to official app stores, plenty other distribution options exist. For example, insurgents are already promoting simple browser-based games to depict Sunni fighters blowing up Iranians or attacking the Saudi government.

Of course, the line between violent propaganda and video game experience has never been perfectly clear. Back in 2002, the US Army spent $32.8 million dollars developing a free-to-play video game to serve as a recruiting tool for the US army. Not to be outdone, Hezbollah released a low-budget first-person shooter Special Force, in which the player fought the IDF.

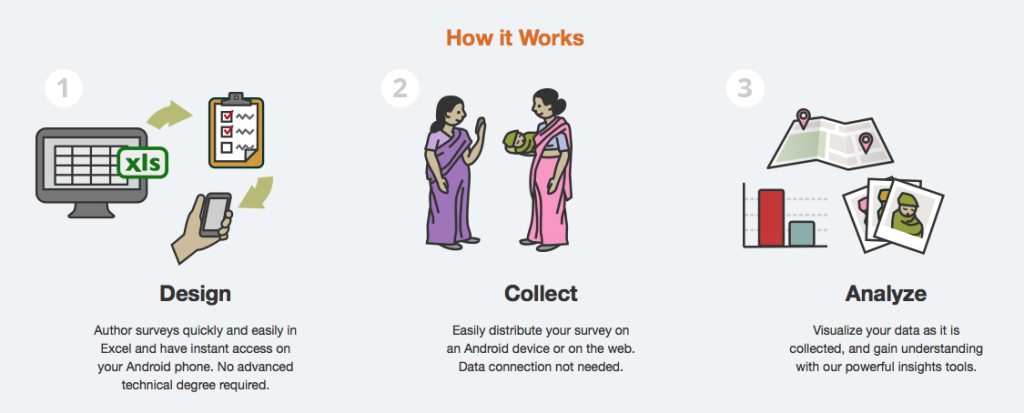

Gaming wasn’t supposed to go this way. Jane McGonigal’s famous 2010 TED Talk on Gaming Can Make a Better World [embedded] encouraged the audience to harness the 3 billion hours a week gaming to solve major problems like hunger, climate change, and violent conflict. McGonigal’s follow-up book Reality is Broken spoke to the 174 million gamers in the United States alone, claiming that “the future will belong to those who can understand, design, and play games.”

But what kind of future will that be?

One possibility is that gaming will experience the same fragmentation as digital media. As games are becoming more accessible to both gamers and developers, concerns are that the role of gatekeepers like Google Play will diminish as gamers seek out experiences that conform to their existing world view. In the same way that social media circles rarely intersect on the topic Gaza (with the exception of a few bridge nodes like Ha’aretz) and community gatekeepers like Wikipedia lock Israel-Palestine pages to prevent vandalism and edit wars, we could be witnessing the phenomenon spreading to video games.

Of course, evangelists like McGonigal have evangelized that the best way to predict the future of gaming is to invent it, and that the beneficial qualities of video games will only emerge if people invest and experiment. Efforts to promote serious games for solving conflict include initiatives such as PeaceMaker, a turn-based computer strategy game that lets players simulate decisions made by the leader of Israel or the Palestinian Authority.

Published in 2007, Asi Burak recently revisited his involvement in the game in a recent interview with Kotaku:

“Perhaps the most important aspect of a game like PeaceMaker is its audacious statement: making peace is as challenging and compelling as making war. Great leaders could break the vicious cycle by boldly asking themselves and their people: are we really taking all the right actions?”

It may be no coincidence that while games simulating violence are simplistic (Drop this bomb! Blow up this IED!), games simulating peacebuilding are often complex and nuanced — as much about teaching a point of view as arriving at a solution. That’s no easy task, but the payoff could be immense. A December 2012 report by the Wilson Center on Gaming Our Way to a Better Future found that in the US alone:

“Video games are a promising route to reengaging these millennials-the 46 million 18- to 29-year-olds who constitute the largest generation in the nation’s history.”

The report concluded with a quote from President Lyndon B. Johnson on establishing the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in 1967 to address the promise of TV: “We have only just begun to grasp the medium.” As a new venue for change it is reaching only “a fraction of its potential audience–and a fraction of its potential worth.”