One of the challenges of using social media in peacebuilding and conflict resolution is that while it can draw together like-minded people advocating for peace, it can also be used to organize violence just as effectively. Groups like the Islamic State (also known by acronyms including IS, ISIS, or ISIL, and currently dominates large portions of Iraq and Syria) are demonstrating that social media can be used to sow fear and promote their political agenda. Not only are they demonstrating how to do this effectively, they’re also demonstrating how hard it is to intervene when a violent actor has control of the information space.

Once violence has started, the information space — including social media — becomes a proxy for conflict. Ideas are being shared and are competing for a legitimacy among the population. In the case of IS, legitimacy could include instilling a sense of fear, or notions that they can or will play the role of the state. The State Department has made an effort to try to combat IS’s messaging in the Twittersphere, but this is difficult for an institution that has long standing communication protocols and is still adapting to the fluidity of social media messaging.

So, at what level does social media help peacebuilders in an information environment?

Civil society as a powerful source for peace

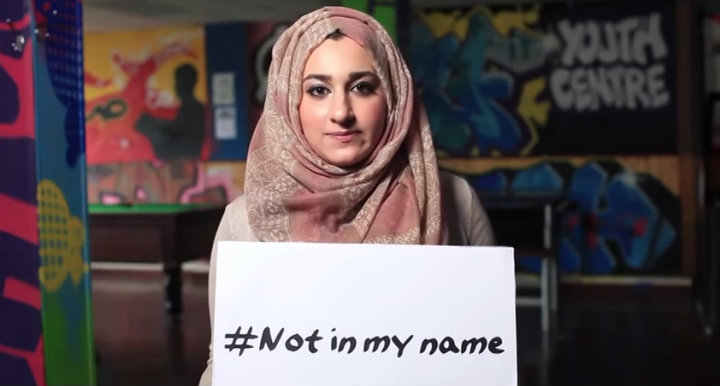

Traditional conflict management institutions may not yet be flexible enough to fully engage in the social media space, but this doesn’t mean that civil society can’t be a powerful force for peace. The Active Change Foundation, a London-based non-profit, set up the social media campaign for British Muslims called #notinmyname. The project uses Twitter to share videos and photos of Muslims, particularly youth, sharing reasons why IS does not speak for them as muslims. The project has gotten over 14,000 tweets using the #notinmyname hashtag, and is flexible in a way that a large institution’s use of social media cannot be. This isn’t to say that organizations like the State Department don’t play a role in social media, but in a highly fluid environment something grassroots like #notinmyname can catch on and respond to IS’s tweets in volume and tone. Winning the information war on something like Twitter depends on both of these and it’s impossible for a single user, even a user as big as the Department of State, to match the size of a social media network like IS’s.

Civil society response with mockery and humour

Another way Muslim civil society is responding is with mockery and humor. What’s important is that these videos and Twitter campaigns are coming from within Muslim communities. Humor has played an important role in protests and movements against dictators and repressive regimes previously, and it can take on a life of its own once it has percolated out into a space like Twitter. Again, this is something that large institutions are going to have trouble instigating. The messages have to be organic and come from within the communities that face the threat of a dictator or a group like IS. Indeed, something like a humor or ridicule protest could lose its legitimacy if larger institutions like the Department of State is involved.

Social media’s power to create grassroots movements across geographies

When we look at the role of social media in peacebuilding or conflict, we have to look beyond just the nature of the message. Social media is just a broadcast tool – it pushes out whatever message the user wants. The important question becomes the strategy employed by the peacebuilding community to engage against the violent messaging of an organization like IS. The power of social media is maximized when civil society bands together across geography, developing a large networked community. How traditional peacebuilding and governance institutions engage with these organic civil society networks is important. Large institutions can help give grassroots movements increased legitimacy and the backing of a recognized institution, but they must also be careful not to undermine the community’s legitimacy when organizing a message of peace in the face of violence.

Interested in learning more about using social media for peacebuilding? Register now for our upcoming Technology for Conflict Management & Peacebuilding online course that runs October 6 – 31, 2014.