This article was first published on the The Asia Foundation’s blog, In Asia.

“Just because they are poor and isolated doesn’t mean they don’t have the potential to be the next Bill Gates,” said Shahed Kayes, the founder of Subornogram Foundation in Bangladesh, while introducing me to lively students at a school he started on the remote island of Mayadip. Located in the Meghna River, the island’s 1,100 residents don’t have access to public services such as safe drinking water, public schools, or health care. The residents rely on the river’s catch of fish for their livelihood, and 97 percent live below the poverty line. Although the school doesn’t own a single computer and the island has no electricity, Shahed couldn’t resist taking out his personal laptop and showing the children how to use it, giving them at least a small glimpse of the world beyond their shores.

While the school on Mayadip only recently acquired rough wooden tables to use as desks, Shahed’s philosophy captures the promise that technology holds to leap over barriers created by geography, social class, and language.

The desire to use technological innovations to improve education in both the developed and developing worlds is undeniably trendy these days. I attended a UNESCO and Consortium of School Networking conference on this topic in Washington, D.C., recently, and there are dozens of similarly themed workshops being held every month. Experiments using technology in education in the developing world are often driven by international funders, domestic companies, and non-profits who hope these innovations can surmount the many obstacles facing severely challenged education systems where rote teaching methods and undertrained, underpaid, and outnumbered teachers are the norm.

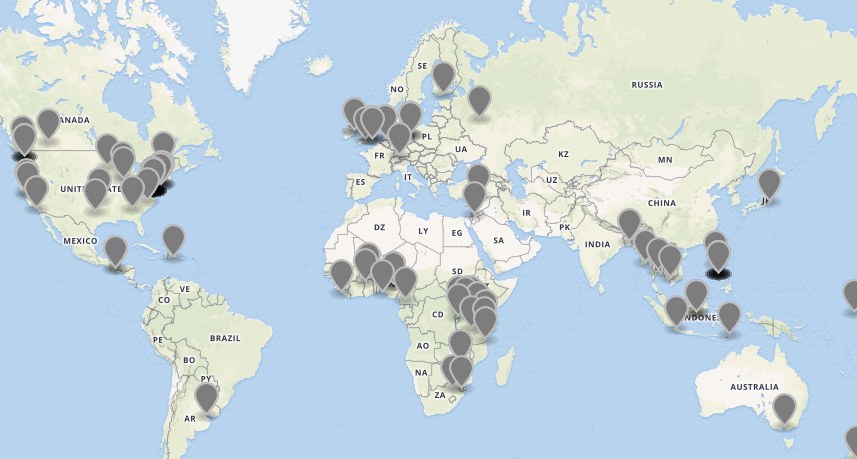

In recent years, Asian governments have made large investments in technology innovations to expand their population's technology capacity. Photo by Bart Verweij.

National governments have also made large investments in this sector with the hope that expanding their population’s technology capacity will fuel economic growth. In Thailand, the government has set aside the equivalent of $60 million to purchase 900,000 tablets through the One Tablet per Child initiative for the country’s 860,000 first graders. The governments of India and the Philippines have been behind efforts to create the world’s cheapest tablets. The National Library of Vietnam reports that while 2,000 people daily walk through the doors of the main Hanoi library, another 5,000 access their online database, compelling the government to invest in digitizing its collections.

And as mobile phone ownership becomes commonplace in the developing world and internet access increases, democratization of information does seems more possible than ever before. In 2010, although the population of Malaysia was 28 million, there were over 30 million mobile phone subscriptions. In the same year, the average Filipino cell phone user sent an average of 600 text messages per month, 43 percent more than their counterparts in the United States. In Vietnam, the internet penetration rate is 31 percent and, in the capitol, Hanoi, penetration is 64 percent. Vietnamese internet use averages about 30 million searches per day. Indeed, when I visited Vietnam last year, I was amazed to find a small rural post office in Duyen Hai overrun by more than 30 eager boys playing educational games and one young girl doing research for a school project, on computers funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through a project with The Asia Foundation and the National Library.

I admit that I can be skeptical about projects I come across that seem to employ technology just for technology’s sake or as a panacea rather than a tool. But these early efforts have yielded some important lessons, including the realization that device-specific projects can quickly become obsolete while long-term investments in training, support, and adaptation are necessary for projects involving technology to be effective and sustainable. With these guiding principles in mind, I am energized by the potential that technological innovations hold to create a more level playing field in education, training, and learning across the globe.

With wider application, the following three advances will, I predict, move us toward greater equality in education and radically transform our world:

1. Literacy will increase dramatically and informally through mobile phones. Ambitious adults and children who lack access to formal education will nonetheless be able to increase their literacy through self-paced “learn to read” text lessons via simple cell phones they already own. Imagine what this means for the Asia-Pacific region, home to the largest number of illiterate adults worldwide at 518 million in 2008, according to UNESCAP. An interesting pilot is the SMS literacy project initiated in three districts in Pakistan by UNESCO and Mobilink. Adolescent girls were able to retain newly acquired literacy skills by using mobile phones to receive and send SMS messages in Urdu and copy them into their workbooks over a four-month period.

2. Language will cease to be the barrier it is today because of breakthroughs in localizing content. Exceptional ideas, techniques, and literature will more easily be shared, appreciated, and put into practice across cultures. Computer programmers are rapidly developing sophisticated tools that enable translation between languages at lightening speed and, increasingly, even account for cultural nuances in meaning. Although a human touch is still ideal for translation, this technology-driven localization solution will vastly change our lives and break down communication challenges among users of different languages. In the near future it means that students and reformers will more easily access the information they need even if it is not published in a language they speak.

3. Education will become widely accessible, more affordable, and less exclusive. Today, circumstances of birth, income, and geography greatly affect an individual’s ability to access quality education. This is changing rapidly in the higher education sphere thanks to the Open Education Resource (OER) movement and initiatives such as iTunes University and Open CourseWare (OCW). Launched by MIT in 2001 and supported by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the OCW Consortium’s 250 universities and associated organizations from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas offer more than 13,000 college level courses in 20 languages entirely free. The site boasts 133 million visits by 95 million visitors from virtually every country. The OCW Mirror Site Program provides the same content on hard drives to educational organizations with limited or costly internet access.

Distance learning is part of this phenomenon. Increasingly, governments, technology companies, and educators are partnering to upgrade capacity and extend education to remote areas. For example, in Sri Lanka, the cellular company Mobitel and the University of Colombo are beginning to offer post-graduate courses using broadband mobile links to students anywhere in Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

While physical books will remain an appropriate technology for delivering education to our partners in many parts of Asia for years to come, technology’s potential to help Books for Asia meet its mission to improve access to information and opportunity is undeniable as we look ahead. That’s why we are launching a new “Technology Start-up Fund: Access for Asia.” The brand-new fund will support promising projects incubated by our in-country staff in collaboration with creative education organizations, publishers, technology companies, and donors.

Melody Zavala is the director of The Asia Foundation’s Books for Asia Program. She can be reached at mzavala@asiafound.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the individual author and not those of The Asia Foundation.