Cross-posted from The Stanford Social Innovation Review by Roshan Paul and Alexa Clay

This is the second in a series of interviews where we speak with leading innovators who are appropriating lessons from open source thinking—once purely the domain of the software engineer—for social change.

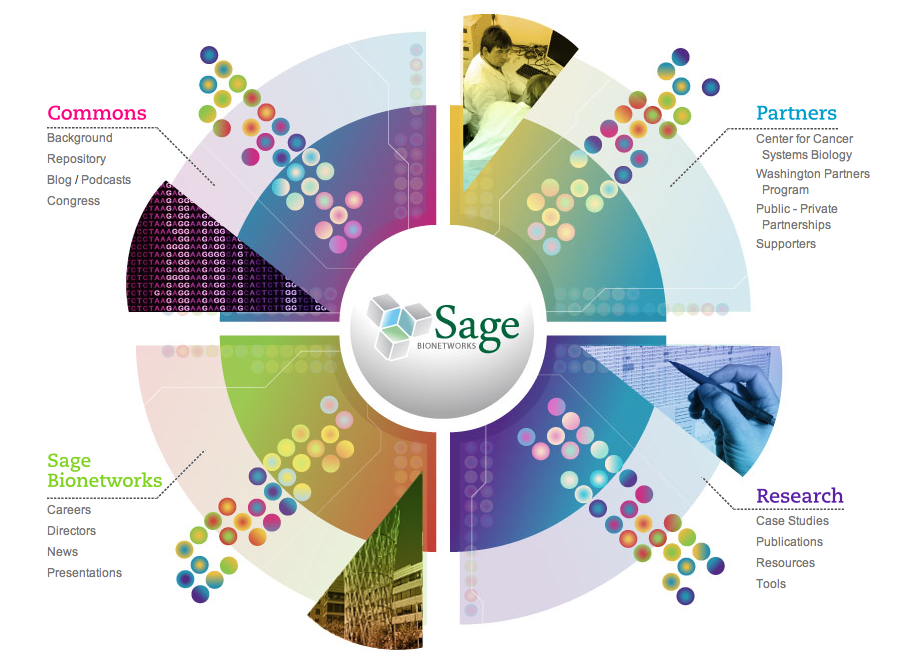

Stephen Friend is an Ashoka Fellow in the United States working to transform the culture and practice of closed information systems present in biomedical research to align with and support health outcomes by establishing a commons. He is president of Sage Bionetworks.

Roshan Paul and Alexa Clay: What is the problem with the current health care research and development (R&D) community, and how are you addressing it? Stephen Friend: The medical information system is closed. Scientists get funded to generate data, then they publish it, and only then do they talk about it. The same is true for R&D in pharmaceutical and biotech companies. The current system is a primitive model, a sort of hunter-gatherer approach. A single researcher or closed team of researchers go after a molecular target or cure in isolation. It’s a them-against-the-world mentality. The “medical-industrial complex” is not incentivized to share amongst each other, let alone with patients.

At Sage Bionetworks, we are building a system where molecular knowledge about diseases can be pooled together from patients, scientists, and physicians. As a result, communities with a specific interest in a disease—say Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s—can bring their data together. Once brought together, the data and models for the disease can evolve as more data is collected. For example, if someone is interested in Parkinson’s, she will be able to track and follow the evolution of the disease model. Imagine a world where citizens could follow disease-related projects, become fans, and join as followers or even funders.

Q: What challenges do you face in building communities of users?

Given that much R&D in the health care sector has happened within the proprietary domain of big pharma or biotechs, there is a cultural shift that will need to happen. Moving from an attitude characterized by competitiveness and proprietary information to one that is pre-competitive and collaborative is a challenge. The good news is that the patients who want better therapies are poised to put pressure on the current siloed, closed system to open it up to exponential open sharing approaches.

Q: You are at the early phases of developing this platform. But what is your vision for it ultimately?

Once there is enough information on the platform, patients paired with doctors will start to shape their own treatments. Take muscular dystrophy (MS), for example. We are considering projects that will bring together hundreds of patients to collect information about the deep molecular characteristics of their diseases, along with all the information about which molecular characteristics respond to which existing therapies. We hope this will allow us to detect molecular classifications that can get the right drug to the right patient. Thus, patients can start to see themselves as active agents in their own treatments, an evolution toward being self-responsible citizens. This will be “the democratization of medicine.”

Q: How are you using open source principles to scale your platform?

For the platform to work, traditional definitions of what a scientist or doctor is, what a citizen or patient is, and what a funder is, need to shift. We’re building a commons—a place where everyone can contribute data, and shape new methods of disease funding and treatment. Eventually, we’ll move beyond just data sharing and create a “virtual marketplace” where funders, scientists, and patients can work together across disease classes.

Q. How do you distinguish between quality and noise?

Similar to Amazon’s Reader Reports and standard consumer reports, we assume that the data that people first enter should not be trusted. We give it all an initial neutral rating. But as people use it over time, the better data has the opportunity to get more popular, acquire a higher quality rating, and thus gain more visibility.

Q: What inspiration do you take from the open source movement?

There’s a great attitude within open source communities that if you assemble enough individuals to collectively problem-solve, you’ll be able to identify amazing solutions. That’s the spirit we have at Sage Bionetworks. We’re inviting all sorts of different participants to collaborate and share clinical/medical information in a collective space. Together with citizens, scientists, and funders we ask: Why can’t we, together, build models of disease in ways similar to those in other open source communities?

Roshan Paul is on the TechChange Advisory Board and is the Senior Change Manager at Ashoka.

If you are interested in learning more about how mobile phones can make a social and economic impact in the developing world, consider taking our three week online certificate course, Mobiles for International Development: New Platforms for Public Health, Finance, and Education.